Over the course of the twentieth century, black people in the United States lost up to 12 million acres of land. They were frequently evicted from their homes and farms as a result of systemic and structural practices used by the USDA, local law agencies, and financial institutions.

Black Land Loss in the United States: From Landowners to Landless

I. Introduction to black land loss

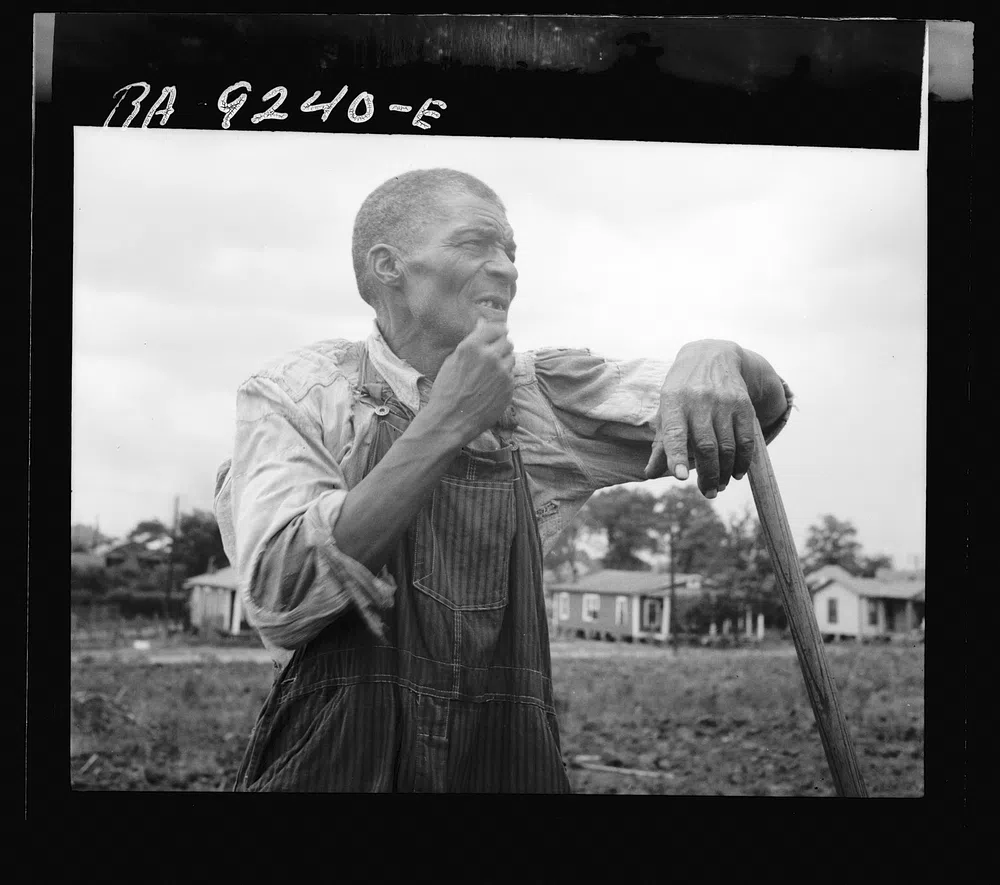

Black land loss in the United States refers to the loss of land ownership and rights by black families and farmers residing or farming in the United States. Just after the turn of the 20th century, black agriculture was at its peak in America. While the eras of Emancipation and Reconstruction were still recent history, African Americans, largely formerly enslaved people and their descendants, had acquired as much as 14 million acres of land across the United States. Black land loss dates back to the mid-19th century, when, in some states, black Americans were prohibited from owning land after the Civil War ended. The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves but did not guarantee a right to land ownership. The “40 acres and a mule” promise would have been the first significant attempt at reparations for recently freed slaves, but Andrew Johnson swiftly overturned it in the early months of his presidency.

Despite increasing segregation and land ownership disputes, black farm land ownership steadily increased in the late 1800s and hit an all-time-high national average in 1910, when 14% of all farm owner-operators were Black Americans. This was in the decades following the Civil War, in which freed slaves and their descendants accumulated 19 million acres of land. During this Reconstruction period, Black landowners purchased every available and affordable plot of land that they could.

The significance of understanding black land loss

Due to the fact that it resulted in the loss of important wealth-creating resources for Black landowners, historical Black land loss is essential for discussion since it has a substantial impact on racial wealth discrepancies.

Lack of ownership is a contributor to the economic inequality that has weakened the black middle class and impeded asset growth and succession.

Importance of addressing this issue

Empowering more African Americans to own and farm land would benefit surrounding communities by strengthening local economies, building more resilient communities, contributing to robust local food systems, and helping to reduce suburban sprawl in rural areas.

II. Historical Context of Black Land Loss

A brief overview of slavery and sharecropping as precursors to land loss

Former slaves sought employment after the Civil War, while plantation owners sought laborers. In the absence of cash and an independent credit system, sharecropping emerged.

Sharecropping is a system in which the landowner/planter permits the tenant to use the land in exchange for a portion of the harvest. This encouraged tenants to produce the largest harvest possible and ensured that they would remain attached to the land and unlikely to pursue other opportunities. After the Civil War, many black families in the South rented land from white owners and grew cotton, tobacco, and rice as cash crops. In many instances, landlords or adjacent merchants would lease equipment to tenants and provide credit for seed, fertilizer, food, and other items until harvest season. At that time, the tenant and proprietor or merchant would determine who owed whom and how much money.

High interest rates, unpredictable harvests, and unscrupulous landlords and merchants frequently kept tenant farm families deeply in debt, necessitating that the debt be transferred over to the following year or years. The laws that favored landowners made it difficult or even unlawful for sharecroppers to sell their crops to anyone other than their landlord, or prevented them from leaving if they were in debt to their landlord.

Two-thirds of all sharecroppers were white, while the remaining third were black. In the 1930s, sharecroppers began organizing for improved working rights, and the integrated Southern Tenant Farmers Union began to gain power, despite the fact that both groups were at the bottom of the social hierarchy. In the 1940s, the Great Depression, mechanization, and other factors caused the decline of sharecropping.

Examples of specific historical events that contributed to black land loss

In 1862, the Homestead Act was passed by the Federal government. The act enabled American citizens to own government-surveyed land and work on it if they applied to acquire it. African Americans, however, were excluded from this land ownership opportunity. Even after the 14th Amendment and the abolition of slavery, no restitution was made to blacks in terms of land ownership.

The Morrill Land Grant Act, which the government passed in 1862, was in every way discriminatory against black people. The act is behind the creation of land-grant colleges, funded by the sale of federally-owned land taken from indigenous tribes through treaties and seizures; white colleges were the sole beneficiaries.

The 1927 Mississippi flood, which in some places was up to 60 miles wide and caused the Great Migration, also had a negative impact on African American farmers. Rescue efforts and responses ordered by the government were directed towards white areas rather than black ones.

Discriminatory lending practices gave unequal loans to land-grant universities for black farmers, and several laws were passed that restricted land to educated white farmers and prohibited people of color from owning land in certain states. Between 1910 and 1997, African Americans lost about 90% of their farmland. One of the main causes of this property loss is Heirs’ Property.

Heirs’ property, where descendants of land owners inherit land from their family but have no will or legal documentation that proves their land ownership, is another major cause of black land loss. The issue of heirs’ property loss still persists today.

In the early 1900s, a white supremacist backlash spread across the United States. During this time period, many black men were lynched because white landowners wanted their land. Violent mobs often beat and threatened to murder Black farmers if they didn’t abandon their homes. Over the course of two months in 1912, a mob drove out more than a thousand Black people from their homes in Forsyth County, Georgia.

III. Current State of Black Land Loss

Recent administrations have attempted to provide some relief to disadvantaged minority groups in the United States; deliberate efforts to alleviate past grievances and dispel the reputation of the United States as a country that mistreats its racial minorities.

For example, the Biden administration offered black farmers loan relief. This step was part of the larger American Rescue Plan Act. The courts, however, halted the move because white farmers saw the act as discriminatory and in violation of their legal rights, so they launched a lawsuit, and the administration cancelled the plan.

Another significant development is the ongoing campaign in America to regulate partition sales and make them viable and useful for black people, rather than negatively impacting their holdings. The Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act is the name of this law. It protects minorities’ rights and allows them to sell their homes as they see fit. Fourteen states have now ratified this law, with the remaining states likely to follow suit soon.

The House recently passed legislation that would allow landowners to get crop insurance benefits from USDA programs in order to produce on their land. The law also allows for loans with simple terms.

Economic implications for black communities and individuals

The land is a major source of wealth that is passed down through generations. It provides safety and dependability. Land is one of the most stable types of investment among viable assets. It has numerous advantages, including inflation protection, passive income generation, multigenerational wealth creation, and portfolio diversification.

Disruption of generational wealth and its impact on future generations

As with the Civil Rights Act, addressing this issue would necessitate deliberate and ongoing efforts at all levels to confront and reverse the trend.